Many farmers have questions when it comes to major industry mergers. We are answering some frequently asked questions here and sharing firsthand insight from some of our whistleblower clients, former poultry growers and current poultry growers.

What does consolidation mean for you?

One significant merger the Department of Justice is considering right now is that of Sanderson Farms Inc. and Wayne Farms LLC, which is expected to create the third largest chicken company in the country. While CEOs make promises to be a better company after the merger, farmers are left wondering what this increasing consolidation really means for them.

Currently, only a handful of corporations control our food from farm to fork. Over the past 50 years, fewer and fewer multinational agribusiness corporations have come to control more and more of our food system, shutting out local and family farmers in the process. With unchecked power, companies have standardized exploitative practices that are harmful to farmers, to rural communities, to the animals themselves and to our environment. In general, this unchecked concentration spells bad news for farmers.

Why would a farmer pay attention to increased consolidation in the poultry and livestock industry?

Because you want to keep farming. Concentration happens in an industry when bigger companies buy up smaller companies to the point that free and fair competition is stifled. When the corporation owns every step in the production of the final product, they can exert tremendous power over the livelihoods of the farmers, workers, and communities whose hard work brings food to our tables. The dramatic imbalance of power between producers and corporations means that farmers increasingly have nowhere to sell in the marketplace except to one or two companies. Corporations are able to manipulate the marketplace, push down the prices paid to farmers and ranchers, and drive independent producers out of business.

Concentration leads to the loss of farms. Despite their promises to be “partners” with farmers, from the company’s perspective, the fewer farmers they contract with the more efficient their system will be. Contract farming models favor bigger and bigger farms, and razor thin profit margins pressure farmers to go further into debt to keep up.

Right now, in the US we produce around 9.5 billion broiler chickens each year. All of these birds are raised on just 25,000 farms. In 1950, there were over 1.6 million chicken farms, raising about 580 million chickens in a year, an average of 363 birds per farm. Between 1950 and today, the industry changed dramatically with the introduction of CAFO housing, vertical integration, and the contract system. Now farms average 330,000 birds per farm and are steadily increasing in size. As farms get bigger, the number of farmers it takes to raise those birds grows smaller and smaller, and more farms are pushed out of the industry all together.

Could this merger lower your paycheck?

With fewer companies in the marketplace, farmers lose the freedom to choose who to grow for. Because the poultry and livestock industry are already so highly concentrated, farmers face many barriers in changing from one company to another. Most companies require specific equipment and barns, and for many farmers switching contracts would involve a significant investment. These types of requirements actively reduce competition among companies for farmers in a region, making farmers dependent on one company and reducing their bargaining power.

Increased concentration in the industry only intensifies this problem. If there is only one company active in your area, then once you are in debt, you will have no choice but to accept the deal they offer you – even if they decide to lower your pay. A USDA study on the impacts of concentration on growers’ pay found that growers in an area with only one integrator earned about 8% less than growers in an area with four or more integrators to choose from. And having few companies to work with is increasingly the trend, as mergers such as Wayne and Sanderson take place throughout the industry. In 2011, 21.7 percent of growers reported only having one integrator to choose from, and another 30.2 percent reported only having two operating in their area. Over 50% of chicken growers already face a highly concentrated and uncompetitive marketplace.

How does concentration impact farmer debt?

With less competition, companies can exert increased power over farmers. In a competitive marketplace, farmers would be able to operate as entrepreneurs. They would invest in improvements to their operation based reasonably believing they would make a return on that investment. In the contract chicken industry, farmers often do not have a choice when it comes to making upgrades to their poultry houses, even if they won’t be able to pay it off or it puts their farm at financial risk. Companies may tell farmers that if they choose not to install new equipment, they will take a significant pay cut. In some cases, the company will even terminate farmers’ contracts all together if they refuse to make mandatory upgrades. Many farmers start out with a poultry contract believing that they will pay it off in 10-15 years but find themselves 30 years or more in the business, still trying to pay off their chicken farm debt, because of required upgrades along the way.

The difference between chicken farming and more competitive agricultural markets shows in the numbers. Chicken farmers carry some of the highest debt loads in all of agriculture, with close to 70% of chicken farms operating in debt. This is a 38% deviation from the national average for farm debt. Hog and dairy operations are a close second and third. As these industries grow increasingly concentrated, companies shift toward having fewer contracts with bigger, more automated, and more capital-intensive farms, driving up farm debt.

I work hard and I know there are always risks in farming. How could a merger like this one impact my business decisions?

There is a basic principle in economics that every farmer already knows. The more information you have, the better decision you can make for your business. You may not be able to control the weather, but you would never plant without knowing the average frost dates in your county. The problem with increasing corporate concentration in the chicken business is that with total control and no competition, companies can hold back information from farmers, keeping them in the dark about basic aspects of the business – like how their paycheck was calculated and how their prices are set. In a business partnership, this situation would be called “asymmetric information” – meaning that one partner has all the info and the other is in the dark. This would be a red flag for a businessman, but chicken companies routinely ask farmers to invest millions based on little more than vague or verbal promises and glossy advertisements.

Farmers across the industry have had to fight for transparency in their contracts with chicken companies. Over time, farmers have been provided less and less information about the nuts and bolts of the business. Are they getting chicks from a good breeder farm? Did the company actually bring the amount of feed they charged them for? Are their birds being weighed fairly? Was there a disease issue at the company hatchery? FIC client and farmer whistleblower Rudy Howell has described how hard it was for him to get truthful and straightforward information about his paycheck from Perdue Farms.

Farmers bring to the table roughly 50% of the capital investment required to produce broiler chickens. For a complex of 500 chicken houses, producing 1.2 million chickens per week, the total cost for processing facilities, chicken houses and all capital investments would be around $180 million. Almost $90 million of that would come from chicken farmers themselves, in the cost of constructing and maintaining the chicken houses. Farmers are treated as equals when it comes to helping them part with their savings and assets, but are not provided even basic information by their business “partner” once the deal is signed.

If the company is doing well, I’ll make more money too if I grow for them, right?

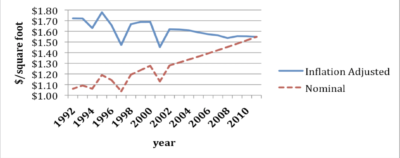

Unfortunately, this is not true. In a theoretically free and fair marketplace, if your business partnership is doing well, you should be rewarded for your investment and hard work by a share of the profits. But the chicken industry has strayed very far from being a free and fair market. Even as company profits have skyrocketed into the billions annually, farmer pay is actually decreasing over time. As farmers are asked to invest more, grow more, and get bigger, they are earning less per pound produced or per square foot of housing provided. Economists Taylor and Domina analyzed decades worth of chicken farm incomes in Alabama and demonstrated that farmers are actually making less of a return on investment over time.

Taylor, Robert and David Domina. (2010). Restoring Economic Health to Contract Poultry Production. May 13. https://bit.ly/3tr9sBS

The key here is to look at farmer pay adjusted for inflation over time. Other researchers have found similar findings in other states. In Arkansas and Oklahoma, farmers received a gross revenue per foot increase from $0.84 in 1979 to $1.62 in 1999, unadjusted for inflation. Once adjusted for inflation, the per square foot revenue payments were the equivalent of $1.69 in 1979 and $1.62 in 1999. In other words, as the industry gets more concentrated and power is reduced to the hands of a few CEOs, real return on investment for poultry farmers is actually decreasing, despite the significant growth and record-breaking profits the companies are bringing in.

Some farmers have told us they are hopeful that Wayne Farms will take over the relationship management with contract farmers from Sanderson after the merger, because they have heard Wayne is better to their farmers. We spoke with farmers who grew for Wayne Farms to learn directly about their experience:

Q: A major issue in this industry for farmers is the truthful, timely delivery of quality feed. Did you have issues with Wayne Farms regarding feed?

A: When the company controls the feed and your paycheck at the same time, you are pretty much at their mercy. If they say they brought you 40,000 pounds of feed, but you feel like your feed bins weren’t actually full, what can you do about it? If the company buys a round of low-quality feed and you start noticing more sick chickens, there’s not much you can do about that either. Their decisions around feed make all the difference in your pay, but they’re no different from any other company out here. They were frequently late with feed, and once even charged me for feed that wasn’t delivered. When they make mistakes, it’s still on your back.

Q: Farmers across the industry have described receiving sick or low-quality chicks taking a cut in their own pay for disease and health problems originating in company hatcheries. What was your experience like with Wayne Farms?

A: Wayne Farms, like Sanderson and others, uses a tournament system to calculate pay. When there are problems with chick health or disease outbreaks, farmers eat the loss. The time you spend culling, the low rank in the tournament because of the loss of feed in the birds that die, all of this comes out of your paycheck.

Q: What was your experience like working with Wayne Farms field techs?

A: Field techs are a big part of your experience of working with a company. At the end of the day, they are the ones you have a relationship with. Techs come unannounced and make changes without consulting the growers. Sometimes they have the birds picked up early.

Q: If these big companies already own everything, how will this merger really affect me?

A: Despite what you may hear from the industry, you don’t have the pick the lesser of two evils. We can demand more.

To download our Fact Sheet for Farmers Considering Company Mergers, click here.